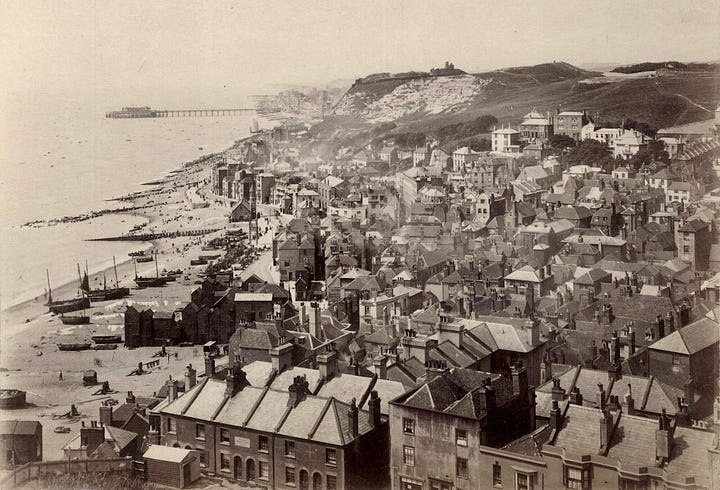

One hundred and thirty years ago, builders buried a Victorian coach house in Hastings, UK, and built my house on top of it. This coach house was part of the courtyard of The Royal Swan Hotel, the largest and most prestigious hotel on the south coast of England.

Over the past four years, more than 1,000 visitors descended through a trap door in my living room floor to explore the coach house underneath, often asking, “What were the builders thinking? Why would they bury a building?”1

Architect Henry Ward, who designed my house and the surrounding streets, never attempted a project like this again, and it’s easy to see why.

The Swan Hotel was auctioned for £9,000 in February 1889 and resold immediately to the Taylor Brothers Builders. Although there is no written evidence of the instructions the Taylor Brothers gave Ward or whether other plans were submitted, they likely asked him for designs that included various house sizes, commercial buildings, and a new hotel. They intended to build and sell all of them within a year.

Ward was 36 years old and ambitious. He'd already made a name for himself with a prize-winning gothic-revival design for a new Hastings town hall and a magnificent church cut into the hillside. However, this was his first time leading an urban renewal project, and it was larger than anything he had undertaken before. The Taylor Brothers may not have been aware that Ward was recuperating from tuberculosis. The pressure was on.

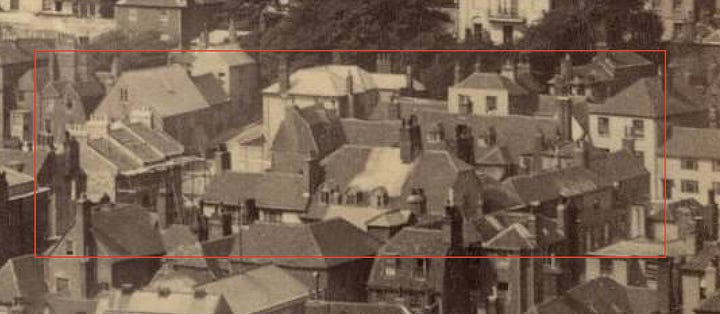

Ward submitted his designs on June 29, 1889, and the planning department approved them just six days later. Among these otherwise meticulous plans was a street layout that, while not sketched on the back of a napkin, lacked any detail on how he'd manage a 30-metre-long and 4-metre-high terrace that ran across the site, with the coach house set against it.

Demolition of the dilapidated barns and outbuildings at the back of the Swan complex began days after the plans were approved.

On November 12, 1889, with construction of the houses underway but much of the old hotel still standing, the Taylor Brothers wrote to the Hastings Planning Department, assuring them that they intended to strengthen the coach house walls before building on top of it. This marked their first indication of a decision to retain the coach house rather than demolish it.

Nine days later, Ward submitted new plans for a cottage on top of the coach house, asking the council to attach these to the already approved designs. Instead of receiving official approval, possibly frustrated by questions from the Planning Department, he wrote "Approved by the Council" on the plans himself and added them to the bundle.

There were glaring problems with Ward’s design - not least that the coach house was not built to support the weight of a substantial brick building. The objective to fit in as many houses as possible on the site complicated things further; in his design my cottage hangs over the front of the coach house rather than sitting squarely on top of it. Ward drew in a lattice of girders to support the weight of the house.

So what was behind his decision?

The Taylor Brothers undoubtedly overpaid for the land and were under immense pressure to sell the properties they built quickly. They borrowed the equivalent of £1.5 million to finance the project and were teetering on the brink of bankruptcy just a year later. By January 1890 they were reduced to selling salvaged door numbers and urinals to pay for the building work. Things got even worse when a 15-year-old boy fell off the scaffolding, shattered his pelvis and died.

Months after Ward submitted his initial design for the street, he had to devise a new plan that added value without increasing costs, all while racing against time and under pressure from the builders and planning department.

Ward’s solution involved casting an elevated concrete platform against the front of the coach house and building two cottages on top of it. Tunnels from a row of shops further down the hill ran beneath this platform to the coach house. This design created extra storage space for each shop and it did away with the need to backfill and level the land. The coach house was buried using demolition rubble from the hotel and the houses on top were built from recycled bricks.

By this point, the Taylor Brothers had run out of time and money, so they ignored the council’s requests to reinforce the coach house walls. The combination of Ward’s ambitious vision and the builders' financial desperation ultimately laid the groundwork for the challenges that would follow and that we would need to put right 130 years later.

Paid subscriptions help support our ongoing restoration efforts. Subscribers can visit the coach house to experience this unique building firsthand.

It seems to me that if they had just filled in the coach house, the walls would not have needed to be strengthened.